【講座側記/Lecture Notes】Ambivalence for Itinerants: Hawkers and Hawker Centres in Singapore

Webinar Title: Ambivalence for Itinerants: Hawkers and Hawker Centres in Singapore

Speaker: Dr Lai Chee Kien

Date: 28 May 2021

Reportage by Dodam Shin (IACS MA student, National Yang Ming Chiao Tung University)

Hawker Culture and Social Spaces in Singapore Webinar Description Hawker Culture in Singapore reflects a living heritage that resonates with people from all walks of life in Singapore. In celebration of the successful inscription of Hawker Culture onto the UNESCO Representative list of Intangible Cultural Heritage, the National Heritage Board will be organising a webinar series on Hawker Culture. This second and final session of the webinar explores: 1) the relationships between hawker culture and social spaces in Singapore, and 2) how this can play a role in promoting community identity and fostering inter-cultural understanding and appreciation in Singapore's context.

Hawker centres are a unique aspect of Singapore culture and lifestyle. They have been feeding generations of people from all walks of life. Dr Chee Kien Lai traced back to the late 19th to early 20th century to explain how Singapore’s hawker culture started. By 1903, because of the growing number of street hawkers, the British colonial authority felt that the hawkers were nuisances along the city streets and had to be controlled and managed. In 1908, the idea of "shelter for the hawker' was first proposed, the first phase of Singapore hawker history began. But due to high budget, it didn't practically take effect until 1908, when the police finally got authority to remove hawkers where street hawking was not permitted by the law.

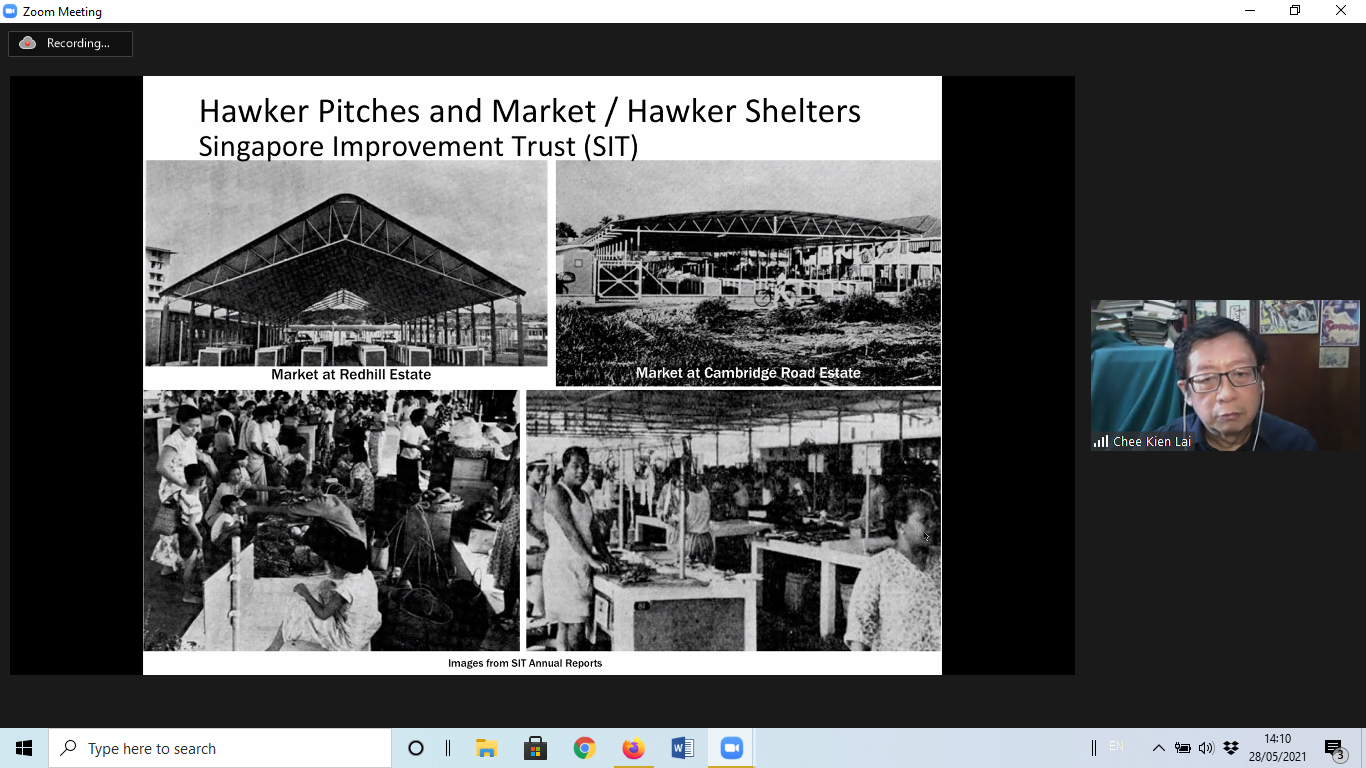

In 1913, the Municipal Health Officer described street hawkers as obstructing streets in the city and wanted to promote the importance of food sanitation. Dr William Middleton, Singapore Municipality's first health officer, divided hawker food items into uncooked food )such as fish, pork, vegetables and fruit), and cooked food. He also made two hawker groups based on size of business, including those big enough to set up stalls on the street, and small businesses carrying baskets, not big enough to set up stalls. He suggested setting up hawker shelters for hawkers belonging to 2b group. The licensing of street hawkers started in 1915. Also shelters for hawkers were built one by one, at Telok Ayer (1921), People's Park (1923) and so on.

In 1950, the report of the hawker enquiry commission stated that “There is undeniably a disposition among officials ... to regard the hawkers as primarily a public nuisance to be removed from the streets.” Many issues, such as access to clean water and concentration of space without proper distance, need to be solved. This led to the construction of hawker shelters in new areas such as Tiong Bahru and Esplanade. After Singapore’s independence in 1965, along with the move to turn Singapore into the region’s business hub, the work of licensing hawkers and relocating them into more organised spaces picked up momentum.

Hawker center history began its third phase in 1971. Between the year of 1971 and 1986, 109 hawker centers were built all over the island, especially in residential areas. In 1972, the government transferred the Hawkers and Markets Department from the Ministry of Health to the Ministry of the Environment (MOE), and renamed it as the Hawker Department with 3 sections : 1) the registration and licensing 2) the planning and development 3) the enforcement section. Agencies and hawkers cooperate with each other for successful resettlement and improving hygiene levels, providing access to amenities such as clean water and proper waste disposal. By the late 1970s, the street hawkers left in the city operated at car park food stalls. They were eventually resettled to new hawker centers built in the city like Cuppage Road Hawker Centre, Maxwell Food Centre, and Newton Food Centre, just to name a few, which later became popular with tourists.

HIstory of hawker centers shows the forces that have shaped hawker culture in Singapore today. Hawker centres ended street hawkers in Singapore and what emerged after the 1970s is a hawker culture that is familiar and celebrated in Singapore. Today, hawker centers play an important role as a community dining room and symbol of Singapore's identity. Its 'openness' and 'publicness' are two distinguishing factors that make it different from food courts commonly built in shopping malls.