【講座側記/Lecture Notes】Decolonizing Indigenous Taiwanese Contemporary Art: An Indigenous Curatorial Initiative

Topic - Decolonizing Indigenous Taiwanese Contemporary Art: An Indigenous Curatorial Initiative

Guest Lecturer: Dr. Biung Ismahasan (Independent curator; PhD in Curating, Centre for Curatorial Studies, University of Essex)

Date: May 18th, 2021

Notes by IACS 0859901 Woo Justina

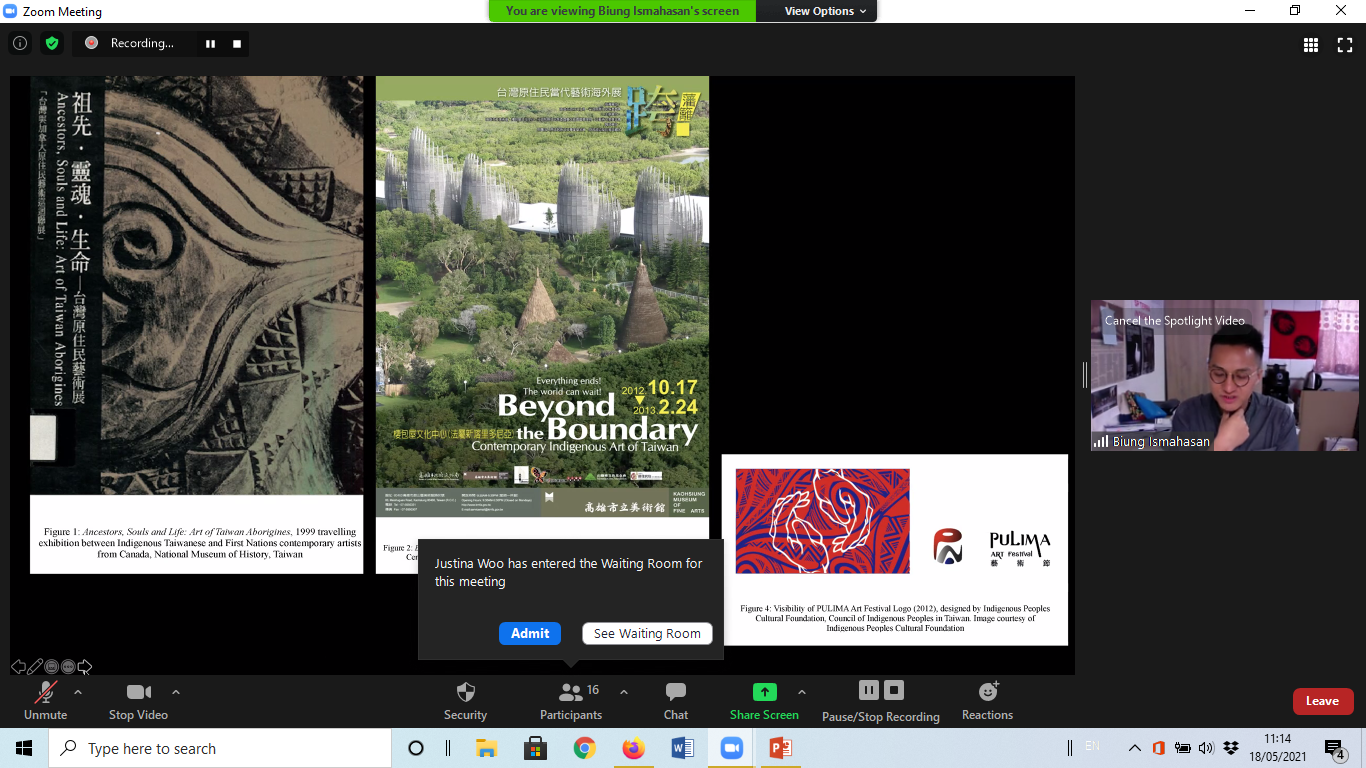

Dr. Biung Ismahasan, a curator, artist and researcher from the Bunun, Atayal and Kanakanavu Nations (three of Taiwan’s sixteen Indigenous Nations), was invited by International Center for Cultural Studies (UST) to present his projects and discuss under the topic of ‘Decolonizing Indigenous Taiwanese Contemporary Art: An Indigenous Curatorial Initiative’. Questions regarding the representations and subjectivity of Indigenous people arose in Biung’s presentation, underpinned that it was imperative to decolonize Indigenous Taiwanese in institutional and/or cultural space. Biung emphasized ‘togetherness’ and solidarity among Indigenous artists from across the globe, and reckoned that contemporary curatorial projects could be a device to curating such ‘togetherness’. Through his curatorial practices, Biung attempted to shed light on the production of knowledge about curatorial decoloniality by maintaining ‘an Indigenous-centrism as a counterpoint’. Stating that Indigenous material in Taiwan was often interpreted, displayed and collected by non-indigenous scholars and curators with Western colonial ideology, Biung began his presentation by mentioning the hegemonic roles of cultural anthropologists, sociologists and historians who partook in aesthetic discourses in Taiwan. In addition to these discourses, he pointed out that an institutional separatism existed between curatorial practice and curation. This alluded to the ongoing question of the subjectivity of the Indigenous people in the aforementioned representations. He further explained such subjectivity stemmed from the arguments of sovereignty, a notion appropriated from the English language. Taking into the account of subjectivity and sovereignty, Biung adopted maluskun mas dalah as his curatorial methodology, a Bunun concept of co-existence or land which also meant ‘humility and fear towards the earth, and like many First Nation cultures, posits a grounded relationship both culturally and spiritually – as sovereignty.’ Michael Walling, the director of Border Crossings’ ORIGINS Festival that currently showcases Biung’s latest exhibition online, responded in an introduction video to Biung’s exhibition with a concise question, ‘does the land belong to us or do we belong to the land?’ In Biung’s collaborative curatorial project from 2014 to 2019 Dispossessions: An Indigenous Performative Encounter, it was not only a curation of trans-Indigenous in different spaces that facilitated relations between Indigenous-to-Indigenous cultural exchange and collaboration, the curatorial project also demonstrated an attempt of non-colonial curatorial practices through collaboration. The traumas, the stigmas of alcoholism, shamanism, healing and transformation shared and experienced by Indigenous people crafted artworks and performances that embodied painful yet humble and spiritual perceptions, and artistic yet political statements. Through curating independent or collaborative artworks and performances together, Indigenous people honored their ancestors and land in institutional cultural spaces as a resistance to identity erasure, initiating alternative senses and a visualization of ‘togetherness’ that subverts colonial practices. One of the most prominent examples of it would be Biung’s Anti-Alcoholism in 2017 in which he interpreted the collaboration as Indigenous Performative Curatorial Practice. In Anti-Alcoholism, Biung tells a deeply personal story and connects with other tribes of Indigenous people by collaborating and incorporating dance and arts performance into his own work. Alcoholism was then taken further as a point of encounter at the Dispossession exhibition at Goldsmiths, London in 2018 where Indigenous Taiwanese Truku and Indigenous Northern Sámi from Norway were invited to collaborate together, creating a performative encounter between the two. In their performances, the vulnerabilities and complexities of their identities and violent past were shown through in moments they performed individually or together as a duo. Moments such as when the artist from the Northern Sámi drank millet wine as a performance and poured a bowl of liquids onto herself as her interpretation of alcoholism, or when she later joined by Indigenous Taiwanese artist from the Truku, stomping their feet together while singing songs in their own languages simultaneously, as if making themselves completely seen and heard while connecting with each other. From Biung’s presentation of these artworks and performances, it depicts a ‘togetherness’ between the Indigenous people and the earth/land through ritualistic performances and installations, as well as a ‘togetherness’ between tribes through performativity. Biung asserted that such Indigenous Performative Curatorial Practice was also an experiment of sociability and sensual experiences of Indigenous people in institutional cultural spaces. He closed the presentation by his latest exhibition Resurgence and Solidarity: Indigenous Taiwanese Women’s Art in Pingtung, in which he had brought his curatorial practice to Taiwan Indigenous Peoples Cultural Development Center. Apart from sovereignty of Indigenous land, the exhibition largely attended to female activism, female resistance, and, bodies, cultures and communities illustrated by artworks filled with textures of fabrics and yarns, weaving an ‘artistic unity’.